(Another) great disturbance in the force

Heinz Siegfried Wolff, scientist and broadcaster, born 29 April 1928; died 15 December 2017

2017 will mark the passing of a significant ‘influencer’. Someone who not only showed that science is interesting but also that it can be fun. Sadly, the name Heinz Wolff will need to join those of Carl Sagan, Hans Rosling and Jonas Salk.

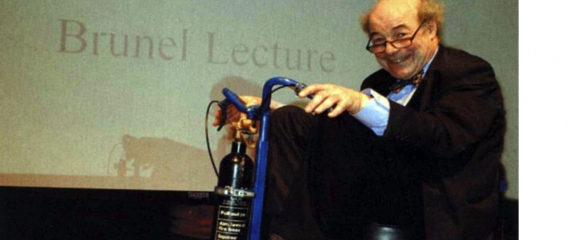

Heinz presented BBC2’s The Great Egg Race. With his trademark bow tie, mad scientist look and his characteristic odd syntax and pronunciation he openly displayed his appetite for invention. His looks and manners helped fit him neatly into what the public would percieve as an “eccentric egghead”, and in many ways he cheerfully exploited the image. However, he was a serious, committed scientist and spokesman for science.

Heinz was born in Berlin, and grew up at the time of the emergence of the Nazi movement: he was later to recall that, at the age of five, he asked his father, Oswald, a volunteer in the first world war: “What is a Jew?” The Wolff family considered themselves Germans and his father used an understanding of business law to help fellow Jews get around the currency laws and escape. The Wolff family fled Germany and arrived in Britain on 3 September 1939, the day the second world war was declared. Heinz commented “We really cut it rather fine,” when he appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs in 1998.

After attending the City of Oxford school, he entered science as a lab technician at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. His work for the Medical Research Council started in the physiology division of the National Institute for Medical Research, and he went on to take a degree in physics and physiology at University College London. By 1962, he was head of the institute’s biomedical engineering division and had embarked on his lifelong passion: the engineering of solutions to human problems. Wolff became one of those scientists who made things happen: he joined the European Space Agency’s life science working group in its early years (1976-82), he advised the British National Space Centre and he served on the board of the Edinburgh international science festival.

In 1983 he founded the Brunel Institute for Bioengineering, now housed in the Heinz Wolff building at the university, and in the course of a research career authored or co-authored around 120 papers in scientific journals. Fans will remember fondly The Great Egg Race, which he hosted from 1979 to 1986. Thousands of young viewers must have been inspired to take up careers in engineering or research. Although the programme began its life with a simple challenge: using the kinetic energy stored in a rubber band, how far could you propel an egg? It developed. The creativity displayed using makeshift tools and improvised gadgets will have prepared many for their own research and PhD studies. Wolff was later to remark that one could make a low-friction bearing with a knitting needle and a pickled onion.